SAN ANTONIO – Editor’s note: This content was created exclusively for KSAT Explains, a new, weekly streaming show that dives deep into the biggest issues facing San Antonio and South Texas. Watch past episodes here and download the free KSAT-TV app to stay up on the latest. This week’s full episode will be available to stream on Oct. 1.

The Alazan Apache Courts have been in the heart of San Antonio’s West Side for nearly 80 years.

The origin of the courts can be traced to 1937 when the U.S. Housing Act passed under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration.

Less than a year later, the courts became the first public housing units to be authorized in the country under the new law, which provided for subsidies to be paid from the U.S. government to improve living conditions for low-income families.

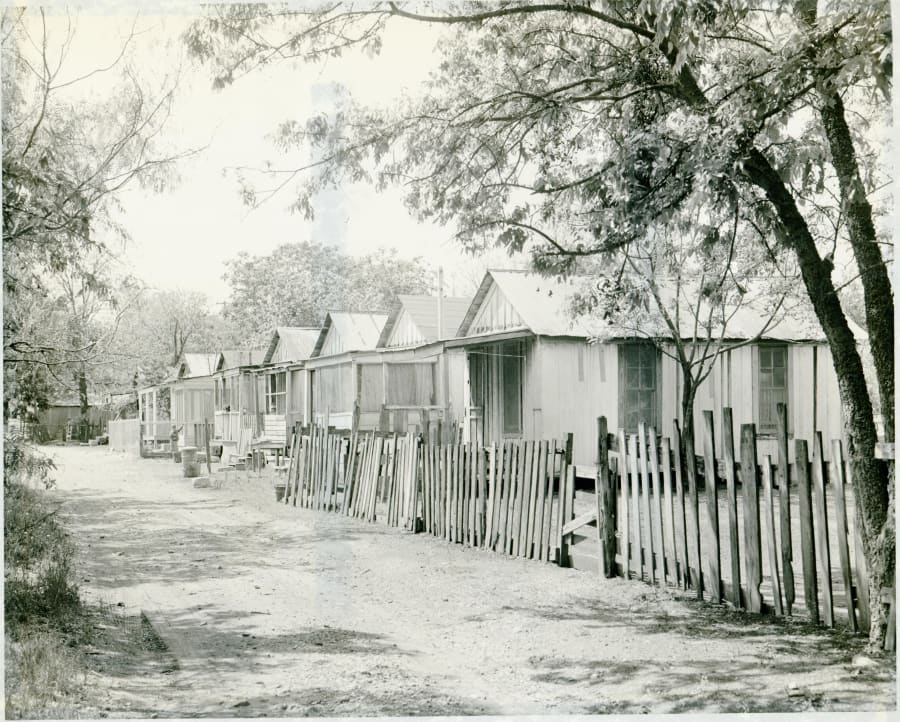

There was a great need for public housing on the West Side.

Residents there, mostly of Mexican descent, did not have running water, paved roads or any drainage and sewage systems.

And many had been left homeless in 1921, after the great flood of San Antonio wiped out small houses and destroyed what little property residents had.

“Folks who were very poor on the West Side lived in little wooden houses and those little houses just got washed away,” said Sarah Gould, interim executive director of the Mexican-American Civil Rights Institute. “And so among those 50 lives lost were a number of babies who were just washed out of their cribs. It was devastating.”

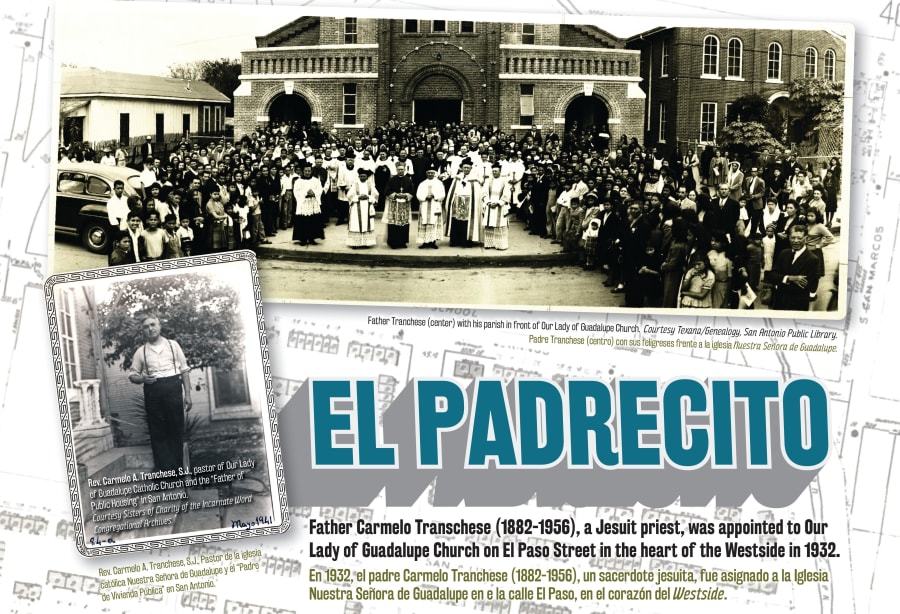

In the early 1930s, social worker and priest Carmelo Tranchese moved into the West Side and immediately rallied city and state leaders to get residents help.

Tranchese also met and wrote letters to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to get the final plans for the Alazan Apache Courts pushed through.

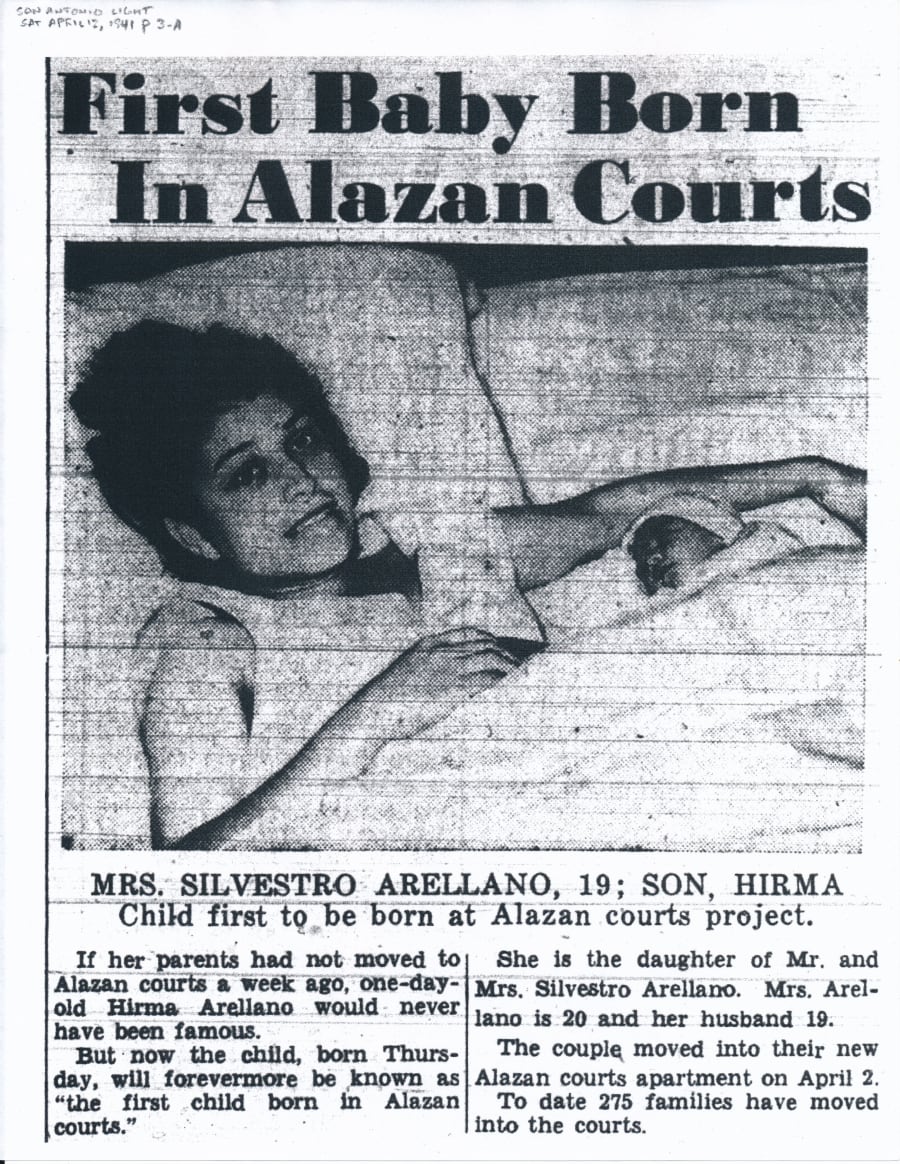

The courts were finally built between 1940 and 1941 and changed the lives of thousands of West Side residents.

“Public housing meant we’ve got to connect it to the city’s sewage system. We’ve got to create sidewalks. We’ve got to create all this infrastructure that has been missing,'” said Gould.

When the Alazan Apache Courts opened, 5,000 people moved into 1,180 units. Those new residents saw a dramatic improvement in living conditions.

The presence of the courts also improved the overall living conditions for West Side residents who did not live there.

“It was just a huge step forward for the West Side in terms of providing that very critical safety net,” said Gould. “The idea was you give them a hand up and then they’ll be able to move out and move on and have their own successful life.”

With Texas still racially segregated, the courts were only open to Mexican-Americans.

Residents had to be U.S. citizens, show an annual income and pay monthly rent. The public housing complex provided them with both shelter and a sense of community.

“They had scouts chapters there. They had all kinds of sports teams, boxing, baseball, basketball,” said Gould. “They had little libraries within the community rooms there.”

The courts also had a unique design that represented early Mexican-American culture.

They were designed by famous San Antonio architect N. Straus Nayfach who was inspired by his travels to Mexico.

“The architecture has significance to the history of the city and the history of our biculturalism here,” said Gould.

Nearly eight decades later, the influence the courts have had in San Antonio can not be overstated.

“Los Courts,” as they have been called, shaped and nurtured generations of West Side families.

“I don’t think it’s any exaggeration to say that the West Side is the corazon of Mexican-American San Antonio,” said Gould.

The courts have been home to several iconic San Antonians. South Texas singers and performers like Eva Garza and Gloria Rios once lived there.

Longtime Bexar County judge Al Alonso, and community leader and founder of Avance, Inc., Gloria Rodriguez, grew up at the courts.

They are just a few of the people from the Alazan Apache Courts that are the fabric of the West Side community.

“So many important cultural organizations have come out of the West Side. People who have embraced and helped embed Mexican-American culture within this city and also taken it to a national level,” said Gould.

Today, it’s no secret that the courts are in need of improvement. They are small, rundown and do not have central air. Their future is in limbo because of redevelopment plans for the area.

Still, the public housing development has been a stepping stone for many San Antonio families.

“We’ve heard so many stories about, ‘my parents were raising six, seven kids. We all graduated from high school. We all went on to have these careers,’” said Gould.